Lang. Identification in Code Mixed Text - Lit. Review 1

I am reviewing the literature available on language identification for multilingual documents, focusing on Indic languages. I’ll try to cover it in chronological order, but there might be a few misses here and there. After a decent coverage of the research, I expect to have enough understanding to discuss the challenges present in this task in a code-switched setting and its importance.

What is Language Identification, you ask?

Code-switching (and code-mixing) is the use of two or more languages in a conversation often employed by multilingual users in informal media like personal chats, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit. Language identification in the code-mixed text is the process of labeling each word with the language it belongs to. For example, in a Hinglish text (code-switching between Hindi and English), a sentence like Hindi ke liye it makes no sense should be labeled as Hindi\Hi ke\Hi liye\Hi it\En makes\En no\En sense\En.

- 2013 - Labeling the Languages of Words in Mixed-Language Documents using Weakly Supervised Methods (*this post*)

- 2013 - Query word labeling and Back Transliteration for Indian Languages: Shared task system description

- 2014 - Word-level Language Identification using CRF: Code-switching Shared Task Report of MSR India System

Publication

Labeling the Languages of Words in Mixed-Language Documents using Weakly Supervised Methods

Summary

- It formulated the task of language identification in a multi-lingual document as a sequence labeling problem.

- It used weakly supervised or semi-supervised models for sequence labeling due to the scarcity of available data.

- They found CRF trained with Generalized Expectation (GE) criteria performing the best.

- The experiments showed that the best predictors were {1,2,3,4,5}-grams and the individual word.

- It is the first research work that discussed the identification of languages in multi-lingual documents.

Key Challenges Addressed

- Minority languages: While building language resources for the minority (or low-resource) languages using webpages, the authors noticed that majority of the webpages that contained text in a minority language also contained text in other languages. It was problematic because the data collection method they were using to build the resources would have also scraped multi-lingual documents into one corpus for a single language and would have led to incorrect and noisy downstream language resources.

- Sparse or impoverished training data: Minority languages lack proper digital presence and thus, in turn, have less annotated training data for the language identification systems to train on. The authors have tackled this issue with the use of weakly supervised models trained on small datasets (a few thousand examples) where they down require a lot of labeled data.

- Multilingual documents: With the increase of multilingual users on the internet, a lot more digital content is generated where multiple languages are used, albeit with varying levels of language usage. Identification should work well even in documents with an imbalanced language distribution. For instance, a document with 3% French, 95% English, and 2% Italian.

Constraints/Assumptions

- To keep the manual annotations reliable, they only considered the documents containing words only in two languages.

- Since the two languages present in the documents are known, models are also aware of the two languages a priori.

- Generally, for sequence labeling tasks, we can assume each sequence (not individual tokens of a sequence) as iid on some distribution common to all documents, but we cannot assume this in language identification as one document might have 90% of its words in Hindi while another might only have 20%. Thus authors have made the simplified assumption that sequences within a document are iid. So, the authors considered each token within a sentence as iid.

- The problem becomes trivial when scripts of languages are different, and hence only the languages with a Latin orthography are chosen.

- Only training data is a small amount of monolingual text for each language. It is assumed that there are no annotated sequences available.

Dataset

Following are the 30 languages covered by the researchers divided by continents:

- Africa: Lingala, Malagasy, Oromo, Pular, Fulfulde, Somali, Hausa, Sotho, Tswana, Igbo, Yoruba, Zulu

- Europe: Azerbaijani, Lombard, Basque, Cornish, Croatian, Czech, Serbian, Faroese, Slovak, Hungarian

- Asia: Azerbaijani, Banjar, Cebuano, Uzbek, Kurdish

- North America: Nahuatl, Chippewa, Ojibwa

- Australia: Kiribati

Training Data

They collected the Monolingual samples for all the 30 languages from the following four sources:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Non-English Wikipedias

- The Jehovah’s Witnesses website

- The Rosetta project

To mitigate the varying availability of tokens of the language samples while creating the training data, an equal number of words were sampled from English and each of the second language.

Evaluation Data

-

Data Collection: The BootCat Tool collects webpages on a language by repeatedly searching for the language-specific seed words. Out of all the collected documents, they manually retained only those webpages which just had English and one of the above languages. The dataset is available at: mixed-language-annotations-release-v1.0.

-

Cleaning

- Stripped of HTML

- Converted to utf-8

- Replaced HTML escape sequences with utf8 characters

- Discarded the documents with encoding errors (mixed encodings)

-

Annotation: Following are the annotation rules mentioned in the paper:

- Well-digested English loanwords and borrowings -> foreign language;

- Ordinary proper names (like “John Williams” or “Chicago”) -> language in the context;

- abbreviations (like “FIFA” or “BBC”) -> language in the context;

- Common nouns (like “Stairway to Heaven” or “American Red Cross”) -> language of the words they were in;

- Abbreviations that spelled out English words -> language of the words they were in;

- If language use was ambiguous -> annotator’s best guess;

- Numbers or punctuation -> no label.

The average inter-annotator agreement on a few hundred words from each of the eight documents was 0.988 with 0.5 agreement expected by chance for kappa of 0.975.

Methodology

Baseline Setup

- Objective: Language identification (through classification) of a word, ignoring the fact that it is the part of a sequence. Using this method, the authors want to evaluate various features and classifiers.

- Training Data: Uniformly sampled 1000 words with replacement for appropriate language.

- Eval Data: It is not mentioned what data was used to evaluate these models: either the annotated data itself or other sets of uniformly sampled words from selected languages. Most likely, it’s the annotated data created in the evaluation data section above.

- Classes: Again, it is not clear from the text if they trained a single classifier to classify into all the languages or created 30 different binary classifiers. Although, based on the a priori knowledge of two languages assumption, I think it’s the latter with two classes being

englishandforeign lang. - Feature Engineering:

- character unigrams

- character bigrams

- character trigrams

- character 4-grams

- character 5-grams

- full word

- Feature Selection:

- They trained a logistic regression classifier to find the best set of features.

- Using all available features - {1,2,3,4,5}-grams, and the word - gave the best accuracy score of 0.88 on the data.

- Model Evaluation:

- The evaluation metric is the accuracy.

- Models were evaluated for varying training sizes from 10 to 1000.

- Model Selection:

- Models considered: Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, Decision tree, and Winnow2.

- MALLET was used to train all the above four classifiers on the training data using the best set of features determined in the feature selection step.

-

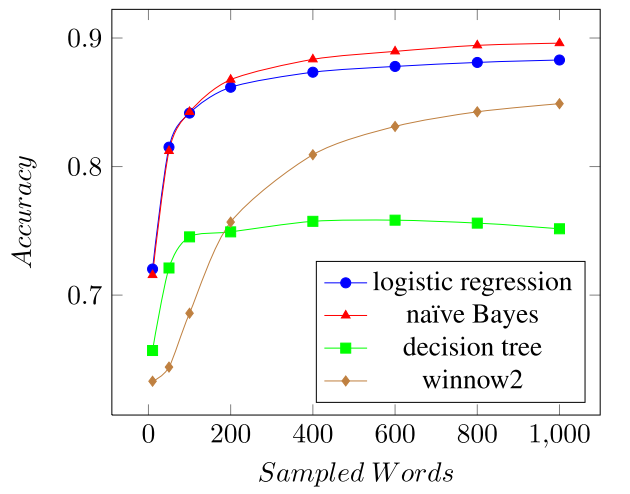

The best model was naive Bayes with the performance shown in the below plot of learning curves for all the four models as the training size changes from 10 to 1000.

Main Task Solution

- Objective: Language identification of each word in a sequence of words from a document.

- Training Data: Monolingual labeled data for English and the selected foreign language.

- Eval Data: Hand annotated sequences from the multilingual documents (discussed here)

- Classes: Not mentioned, but I guess, they trained 30 different models for each foreign language with binary class classification into two categories:

englishandforeign lang. - Preprocessing Steps:

- Word boundaries were defined by punctuation or whitespace

- Excluded tokens containing a digit

- Feature Engineering: In addition to the {1,2,3,4,5}-grams and the whole word as features, to provide some sequence-relevant information they added the following two features:

- Feature for each possible punctuation/digit between previous and current words.

- Feature for each possible punctuation/digit between current and next words.

- Model Selection:

- Due to limited training data and different nature of training and evaluation data (more labeled monolingual vs. less labeled multilingual), the following weakly and semi-supervised models were implemented:

- Linear Chain CRF trained with Generalized Expectation criteria (best performer)

- HMM trained with Expectation-Maximization (EM)

- Logistic Regression trained with Generalized Expectation criteria

- MALLET was used for training.

- Due to limited training data and different nature of training and evaluation data (more labeled monolingual vs. less labeled multilingual), the following weakly and semi-supervised models were implemented:

- Model Evaluation:

- The evaluation metric is the accuracy.

- Models were evaluated for varying training sizes from 10 to 1000.

- Naive Bayes classifier (best performing) from the baseline setup was used to compare all the other models.

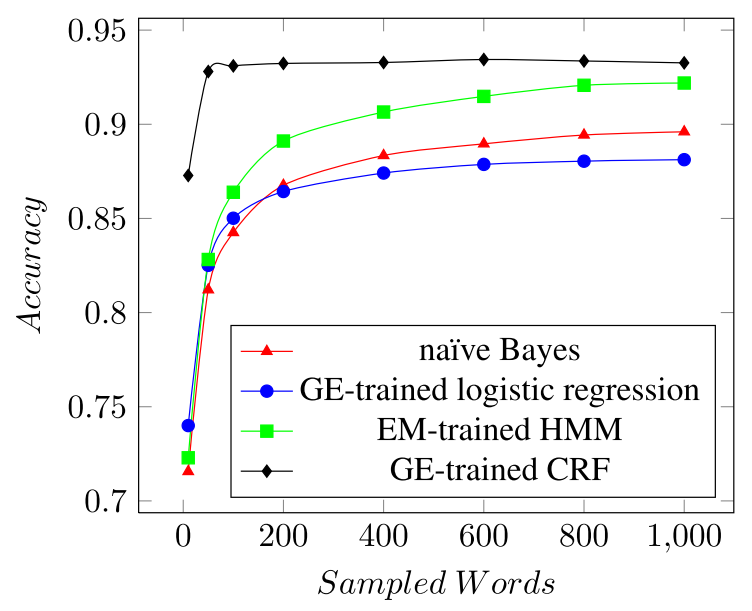

- The best model was CRF trained with the GE gave a consistent performance. The performance of other models is in the below plot of learning curves as the training size changes from 10 to 1000:

- Error Analysis:

- Named Entity errors, possibly because of arbitrary rule decided during the annotation

- Shared word errors, possibly because of arbitrary rule decided during the annotation

- Other remaining errors

Insights/Thoughts on the paper

- The problem was formulated as a sequence labeling problem. Can it be defined in some other way?

- The problem becomes trivial if languages present in the document do not share the character set. Can we somehow convert our complex problem into a trivial one? There are two reasons for two different languages in a document having the same script:

- Both languages share the same native script.

- One language is transliterated into the script of the other language (usually, the dominant language in the document)

If it’s the first case, then we have no way of making the problem trivial, but if it’s the second case, then we can back-transliterate the language into its original script thus, making the labeling task trivial. Although, now a new challenge arises: identifying which word should be back-transliterated. It requires identifying the language of the word, and we are back to the original problem we started with unless we have a magic back-transliteration model which just takes a word and gives a legit back transliteration in the correct language. To my knowledge, there is no such model as of yet.

- The authors conducted some amount of feature engineering, and also did a thorough evaluation to select the optimal feature set.

- Since with small training data we have achieved a decent accuracy, this process should be easily scalable in the production environment for multiple languages.

- The system should have high throughput, as the classification is built with simple features and compute efficient models.

- How is it weakly supervised?

- Models are trained on two monolingual example texts thus only learning to classify a word into one of the two languages.

- Any sequential dependencies between words must be learned by the model on its own because of the lack of any particular features which might inform the model about the dependencies.

- The inference is done on the sequences from a multilingual document.

- How to properly handle Named Entities (NEs)?

- We can create a separate classification category for NEs within our language identification system.

- We don’t evaluate on NEs, but for this, we need to know which tokens represent a NE.

- We use a language-independent Named Entity recognition system in our language identification system.

- What is the model performance for each language independently? It wasn’t clear from the paper if they trained a single classifier or created 30 different models. If it was just one model, then we also need to study its performance on individual languages. If it’s the latter, then the results presented in the publication are averaged over 30 models, and we should explore each model’s performance.

-

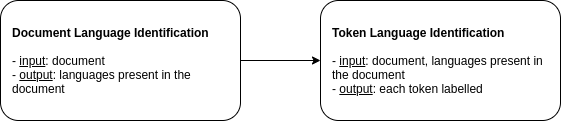

The authors wanted to cover as many languages as possible for the language identification task, so they specifically talked about the dependence on a priori knowledge of the languages. And because of the dearth of data, only 30 languages were evaluated. How do we extend the system for thousands of languages where each document only contains 2-3 languages? One approach could be, first identify the languages present in the document and then use the proposed system trained with the languages determined in the first step to do sequence labeling. Here’s the schematic of this two-level language identification system for any set of languages. Document Language Identification is the identification of languages present in the document, and Token Language Identification is the actual task of identifying each token’s language in that document.

- The publication mainly presented their work on webpages or documents and not on short-text like content generated on social media. Also, the overall concept will remain the same, but the distribution of languages will differ there. And challenges like word normalization will also need to be taken care of.

- Documents in the corpus used for training and inference only contained documents in two different languages having the same native script - Latin. The authors remarked that they saw rare usage of code-mixing in these documents. It might be because of the data collection method they used or the languages they chose to work with. I don’t know what proportion of the actual content on the web could be code-mixed text, but if they had used code-mixed corpus, there’d be more challenges to be solved. Different languages having the same native script might have plenty of unique words; there might not be enough sub-word sharing among the vocabulary of both the languages. Whereas, in code-mixed text, there might be more sub-word sharing that might lead to poor performance. Things might also go in reverse because of the presence of some other patterns models might perform better.

- Any discussions on the transliteration were completely skipped.