Lang. Identification in Code Mixed Text - Lit. Review 2

I am reviewing the literature available on language identification for multilingual documents, focusing on Indic languages. I’ll try to cover it in chronological order, but there might be a few misses here and there. After a decent coverage of the research, I expect to have enough understanding to discuss the challenges present in this task in a code-switched setting and its importance.

What is Language Identification, you ask?

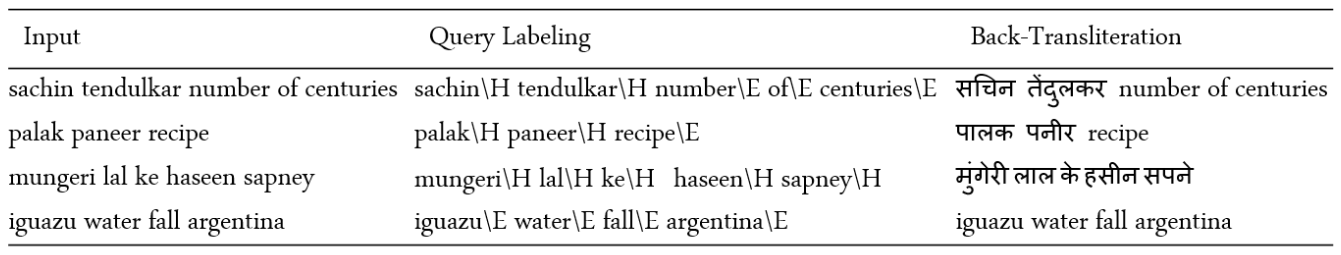

Code-switching (and code-mixing) is the use of two or more languages in a conversation often employed by multilingual users in informal media like personal chats, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit. Language identification in the code-mixed text is the process of labeling each word with the language it belongs to. For example, in a Hinglish text (code-switching between Hindi and English), a sentence like Hindi ke liye it makes no sense should be labeled as Hindi\Hi ke\Hi liye\Hi it\En makes\En no\En sense\En.

- 2013 - Labeling the Languages of Words in Mixed-Language Documents using Weakly Supervised Methods

- 2013 - Query word labeling and Back Transliteration for Indian Languages: Shared task system description (*this post*)

- 2014 - Word-level Language Identification using CRF: Code-switching Shared Task Report of MSR India System

Publication

Query word labeling and Back Transliteration for Indian Languages: Shared task system description

Summary

- The objective is to identify the word level language for Indian languages written in Roman script mixed with the English language.

- They have back-transliterated Indian language words into the native Indic scripts.

- The methodology is to build weakly-supervised models with monolingual samples together with word frequency and context switching probability from Indian language (IL) to English (Eng)

- FIRE-2013 shared task on Transliterated Search targets labeling the individual words of a query with their original language and then also asks to back-transliterate non-English words to their native scripts. The proposed system achieved the best performing results in this shared task.

Key Challenges Addressed

- Indic languages: There is no previous work on building systems for query labeling of text written in an Indian language code-mixed with English.

- Transliterated data: The real challenge comes when the text is in Roman transliterated form, and we are required to label and back-transliterate it. To my knowledge, this is the first paper that tries to tackle both the challenges and create one end-to-end system.

- Sparse training data: Getting the annotated multi-lingual data is expensive and hence not readily available to the researchers. This work tries to solve that by creating models from small mono-lingual transliterated datasets and then using them on the actual multi-lingual data.

Constraints/Assumptions

- All of the languages considered in the publication - Hindi, Gujarati, Bangla - belong to the Indo-Aryan family. This leads to the assumption that the words are pronounced similarly in all three languages.

- Since the model training requires monolingual data in the transliterated form, we assume we have that kind of training data. In this work, task organizers provided this data.

- Since the two languages present in the documents are known, models are aware of the two languages a priori.

Dataset

The three Asian languages covered by the researchers were - Hindi, Gujarati, Bangla.

- Training Data

- Monolingual samples

- Word frequency for all three languages

- Roman transliterations provided as a part of FIRE-2013 shared task

- Evaluation Data

- Labeled code-mixed queries for each language provided in FIRE-2013 shared task

Methodology

Baseline Setup

- Objective: Language identification of each word in a query

- Classes: They trained three different models for each Indian language with binary class classification into two categories:

LI(Indian Language) andEng. - Training Data: Monolingual samples of the languages

- Feature Engineering:

- Character unigrams

- Character bigrams

- Character trigrams

- Character 4-grams

- Character 5-grams

- Full word

- Feature Selection:

- Using all available features - {1,2,3,4,5}-grams, and the complete word - gave the best accuracy.

- For brevity, they didn’t present the evaluation results.s

- Model Selection:

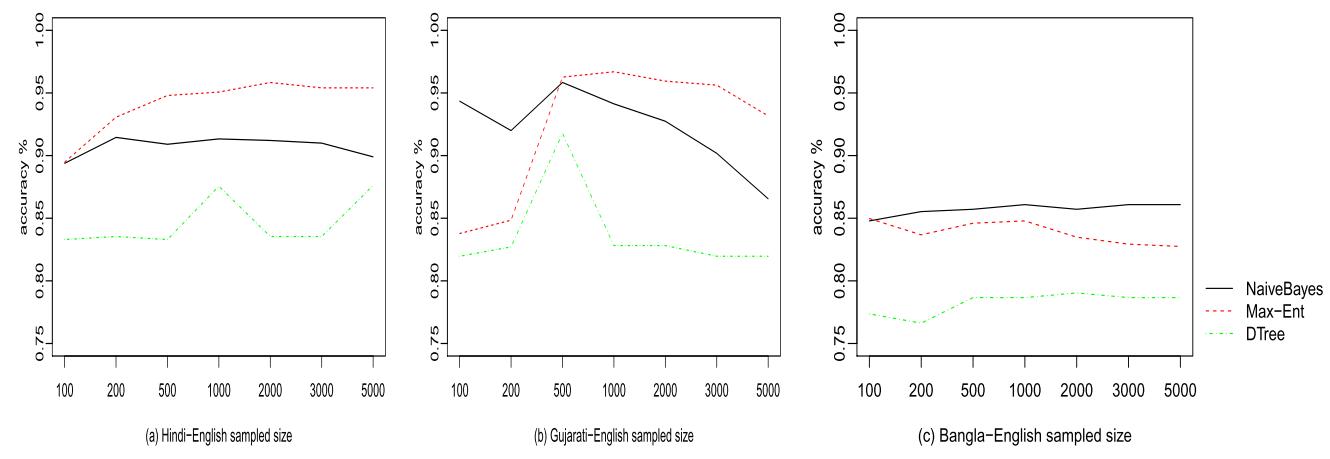

- Models considered: Naive Bayes, Maximum Entropy (Logistic Regression), and Decision tree.

- MALLET was used to train all the three classifiers on the training data for each Indian language using the best set of features determined in the feature selection step.

- Model Evaluation:

- The evaluation metric is the accuracy.

- Models were evaluated for varying training sizes from 100 to 5000.

- For Hindi and Gujarati, the best model was Maximum Entropy.

- Naive Bayes performed better for Bangla.

-

Shown below is the plot of learning curves for all four models as the training size changes from 10 to 1000.

Improving Baseline

- Feature Engineering: In addition to the {1,2,3,4,5}-grams and the whole word as features, they tested the effect of the following two factors on the classification accuracy of the baseline:

- Context switch probability

- Monolingual frequency factor

- Frequency-based Classification: After classifying the token language using the baseline method, get the final label using the below rules-

- Label as

LI, if the classification wasEng, the confidence of word being English is greater than or equal to \(\max({0.98p, 0.98})\) (\(p\) is context switching probability) and the word frequency is less than 20. - Label as

LI, if the classification wasEng, the length of the word is 2 and the word frequency is less than 50. - Label as

Engif the word contains special characters (e.g. &), numerals (e.g. 3D) or the word is all in capitals (e.g. MBA). - For all the remaining cases, the label will remain the same as what the baseline classifier gave for all the remaining cases.

Where, \(C'(w)\) is updated classifier, \(C(w)\) is baseline classifier, \(\mathrm{conf}(E, w)\) is the confidence of word \(w\) being English, \(p\) is context switching probability, \(S\) set of special characters, \(N\) set of numerals, \(A\) set of all capital letters.

There was no explanation in the paper as to how they selected the threshold values and the various conditions.

- Label as

- Hyper-parameter Tuning:

- By varying the context-switching probability \(p\), one can also calculate the optimal context switching probabilities for the model. In the publication, they also show the changes in model accuracies when \(p\) changes from 0.6 to 0.9 for each language.

Back-transliteration

- Objective: Back-transliterate the non-English words of the query to their original script.

- Training Data

- Hindi and Gujarati: Hindi word-list created from monolingual data.

- Bangla: Hindi word-list concatenated with Bangla word-list converted to Hindi using Indic character mapping.

- They couldn’t do the same for Gujarati because very few words were available.

- Model Selection:

- MSRI Name Search tool based on hash-functions for similarity search across domains. [described in the linked research]

- Inference:

- Hindi:

- The MSRI tool directly gives the Hindi transliteration.

- Gujarati:

- Get the Hindi transliteration using the MSRI tool.

- Convert Hindi transliteration to Gujarati using Indic character mapping.

- Bangla:

- Get the Hindi transliteration using the MSRI tool.

- Convert Hindi transliteration to Bangla using Indic character mapping.

- Hindi:

Final Systems

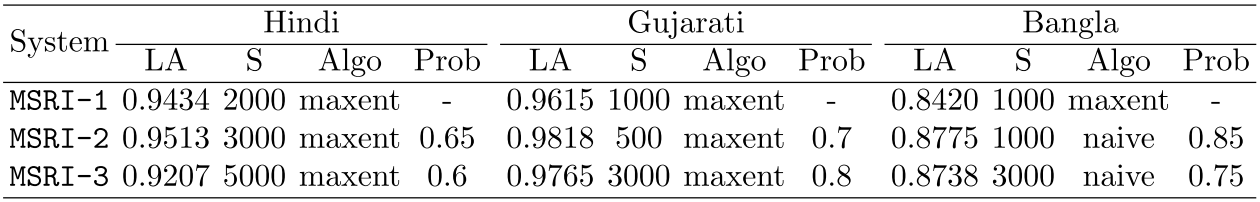

MSRI-1

- Language Label Inference: classifier output + frequency factor

- Back-transliteration: trained on Hindi data

MSRI-2 (Best Performer)

- Language Label Inference: classifier output + frequency factor + context-switch probability

- Back-transliteration: trained on Hindi data

MSRI-3

- Language Label Inference: classifier output + frequency factor + context-switch probability

- Back-transliteration:

- For Hindi and Gujarati, the model is trained on Hindi data

- For Bangla, the model is trained on Hindi+Bangla data

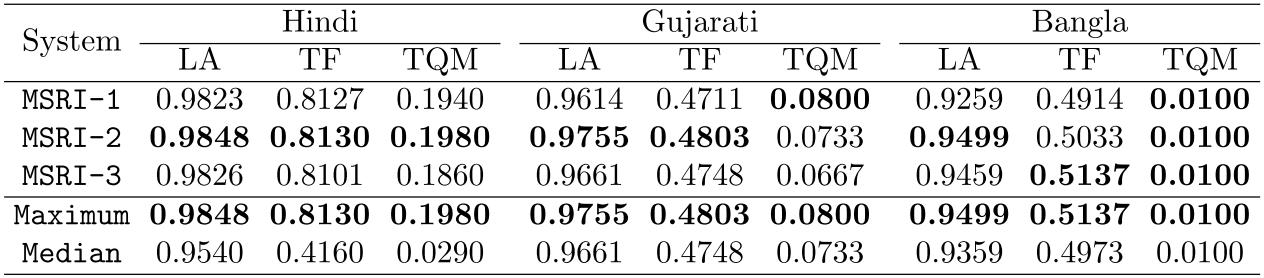

- LA: Labeling accuracy

- Prob: Context probability parameter

- TF: Transliteration F-score

- TQM: % of queries that had exact labeling

Error Analysis

Labeling Errors

- Not enough n-gram information

- Short words (I, ve);

- Ambiguous words (the, ate);

- Erroneous words (emosal).

- Arbitrary rule

- Treating all mixed-numeral tokens as English words (zara2, duwan2)

Back-transliteration Errors

- Phonological variations exhibited by Gujarati and Bangla when compared to Hindi

- In Bangla,

ais frequently pronounced aso. - In Gujarati,

naat the end of a word is sometimes pronounced asnna. - Here, the model trained on Hindi data fails due to slight phonetic differences between Hindi and other languages.

- In Bangla,

- Errors in the development set

Insights/Thoughts on the paper

- The problem was formulated as a sequence labeling problem. Can it be defined in some other way?

- The problem becomes trivial if languages present in the document do not share the character set. In the work, the researchers have tackled the non-trivial problem where even though the languages’ original script is different, because of the use of transliteration while code-switching, the script became same.

- The authors didn’t conduct a lot of feature engineering. They just selected the features proposed in the previous research work and built their systems.

- The model achieved a decent accuracy with small-sized training data. I think the system should be easily scalable in the production environment for multiple languages.

- The system should have high throughput, as the classification is built with simple and compute efficient models, and the back-transliteration system is based on the hash function based similarity search.

- The described process is weakly-supervised:

- Models are trained on two monolingual example texts, thus only learning to classify a word into one of the two languages.

- Any sequential dependencies between words must be learned by the model on its own because of the lack of any particular features which might inform the model about the dependencies.

- The inference is performed on the sequences from a multilingual document.

- Handling Named Entities (NEs): In the previous paper, authors observed many errors because of the wrong labeling of NEs. However, in the current research, the authors haven’t mentioned this issue. Possible reasons-

- Since Indic names have associated meanings and are a part of the vocabulary, the monolingual training data might contain many of the NEs present in the development set provided by the task organizers.

- The development set provided all the language-specific names (Indian names) may be labeled as Indic language words, and thus, the model also learned this pattern.

- The data may not contain many non-Indic NEs like foreign names and places.

- The researchers reported the model performance results for each language, making the adopted methodology lucid. It was not the case in the previous paper I reviewed.

- The authors only covered the three languages which were part of the task. They skipped the discussion of extending the methods for multiple languages where languages might not be similar in pronunciation or not have enough data.

- Since the shared task description aimed to label the search queries, this methodology is suitable for short-text-like content generated on social media. Although language distribution might be different in these queries and social media text, nonetheless, the methods presented here should work, as the models are weakly-supervised, and there is no dependency on the distribution or the context of words. The researchers didn’t discuss and work on challenges like word normalization (misspellings or acronyms) that often pervade search queries and other such sort-form text.

- Queries (or documents) in the dataset given by the shared task organizers only focused on code-mixed data in Latin script. In the previous paper review, I had my doubts if that method will work properly on the code-mixed text. This work employs that same method, albeit, with a few modifications, it was quite successful in the code-mixed text.

- The evaluation of the back-transliteration method wasn’t discussed. With the assumption that there is a pronunciation similarity between the languages considered in this work, the process of back-transliteration became a bit easy where Hindi is the base language, and the other two languages are back-transliterated from the Hindi back-transliterations. This process can’t be adopted when other languages vary a lot in pronunciation or vocabulary. We’ll need to create new methods of doing the back-transliteration. The authors reported the errors the MSRI name search back-transliteration system made, but they didn’t discuss how accurate the system was.